Shadows in the lamplight

(Published in The Hindu, 27 Sept 1992)

My mother and I recently traveled to Adakkaputhur in Palakkad district, deep inside the Malabar region in Kerala, to visit my father’s relatives. It’s a place I'd remembered dimly from my childhood. In my memories, my father’s tharavad, or ancestral home, was a sprawling tiled house on acres of lonely farmland where old people in white moved slowly through the verandas. There was no electricity or running water. When darkness fell, the lamplight threw grotesque shadows on the walls. Beyond the courtyard, foxes howled at the moon.

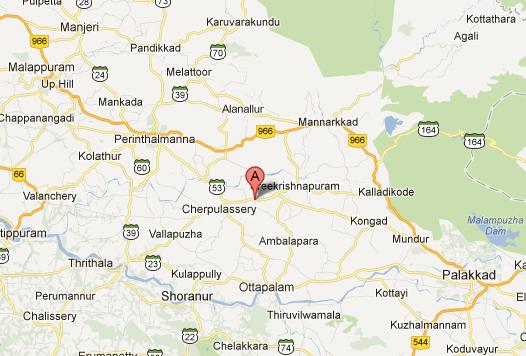

Much of that has changed today. In Malabar at least, the hinterlands are no longer really remote. They are mostly just a bus ride away. But the journey there is still beautiful. To reach Adakkaputhur, you take a bus to Palakkad on roads that are winding strips of tar on an undulating countryside, and get off at Perinthalmanna. From there you board a country bus that rattles you at breakneck speed to Cherpulassery fifteen kilometers away. The roads are narrow, the buses overcrowded and the frayed tarpaulin cover on the window flaps wildly in the breeze. The driver is always in a tearing hurry and you hurtle past green fields and blue hills clutching the seat bar for balance. You get off at Cherpulassery and stretch cramped limbs. You are in beautiful country in the lap of the Blue Mountains. The fields are green with rice sapling and the city is a world away.

Up another bus and down another winding road to my father's ancestral place. Everywhere around you, the celebrated lush green of Kerala. The bus takes a sharp climbing turn and you catch your breath in astonishment. Towering over you, hidden a moment ago, is the stark face of a rock quarry. The granite and mud walls seem to rise vertically out of the green earth. The lorries at its base and the men hanging on scaffolding on the rock face seem incredibly small and brave against the harsh stone. You open your mouth to speak, the bus turns another corner and it’s gone. You blink startled eyes and turn to look again but the hills are once again thick and green. Was it hallucination or was it real?

Three more kilometers down a side road in a neighborhood where everyone, even the bus driver, knows my uncle because he is the Panchayat officer. You get off at a field beside a stile with a few steps leading up to a thorn-covered gate. The stop is simply called officer padi -- the steps leading to the officer’s house. You step over the stile, open the gate and walk along the ridge between fields of green paddy waving in the breeze. Neatly laid irrigation canals brim with water. A thin old man with skin wizened by many summers in the sun herds a couple of buffaloes into the water. A small boy jumps in after them with a shout. When you pass by they stare at you silently and shyly smile.

This land belonged to my father’s family once. Lush green and healthy land, acres of rolling country. The houses and cottages that dot the land formed part of the estate. Does the family own any of it now? My father wouldn’t know. He left Kerala after school and he no longer knows who owns what, and no one’s going to tell him. My grandmother can’t. She’s old and asthmatic and lives in a distant past inside her head. Reform and the new laws have in her own lifetime seen her move from feudal over lordship to being a trustee of an entangled legacy. She now lives in a small cottage with a daughter and a dog. Occasionally her sons drop in to check on her well-being. She will not go with them to the city. We talk of old times and new times.

My mother wants to visit the big house where other relatives of my father stay. I don’t particularly know any of them, our ties are distant, but my mother is a stickler for the disappearing protocols and courtesies of the old joint family system. I borrow my uncle’s motorcycle and double my mother to the big house. This was the house of my childhood memories. The wooden rafters are still grim and the courtyard is still house to a brooding silence. The years have not diminished the house. In a curious way I’m glad. Many times in different places, I have returned to the places of my childhood and they have usually been lesser than I’d remembered. But here, the big house still broods on the farmlands. The mango and jack trees and the inevitable coconut palms cannot soften the severity of its lines nor lighten its demeanor.

But in the afternoon sun, the courtyard is bright and a child’s laughter brightens the murmuring silence. I pass through a darkened room and overcome by a childhood impulse, I flick the lamp switch. Light pours out of a sixty-watt bulb. My cousins laugh when I tell them about my memories of shadows in the lamplight when we were children here together. They thump me on the back and tell me I’ve been away too long. Times have changed, they say.

Of course they have.

And yet. The land has changed hands and now the government, not the landlord collects the taxes. But when you walk on the fields in Adakkaputhur, you still sometimes pause and look back over your shoulder for no reason. This is a deep country and memories are long. The men are indolent, hard, and hint of licentiousness. The women are strong and suffering. At dusk, when night approaches from the darkening hills and when the fields are empty, you tend to walk a faster step to the homestead. The confidence of day is now prey to the uncertainties of the night. And when night falls on the fields and the courtyards of Adakkaputhur, the lamplight still casts shadows in the dark.

Up another bus and down another winding road to my father's ancestral place. Everywhere around you, the celebrated lush green of Kerala. The bus takes a sharp climbing turn and you catch your breath in astonishment. Towering over you, hidden a moment ago, is the stark face of a rock quarry. The granite and mud walls seem to rise vertically out of the green earth. The lorries at its base and the men hanging on scaffolding on the rock face seem incredibly small and brave against the harsh stone. You open your mouth to speak, the bus turns another corner and it’s gone. You blink startled eyes and turn to look again but the hills are once again thick and green. Was it hallucination or was it real?

Three more kilometers down a side road in a neighborhood where everyone, even the bus driver, knows my uncle because he is the Panchayat officer. You get off at a field beside a stile with a few steps leading up to a thorn-covered gate. The stop is simply called officer padi -- the steps leading to the officer’s house. You step over the stile, open the gate and walk along the ridge between fields of green paddy waving in the breeze. Neatly laid irrigation canals brim with water. A thin old man with skin wizened by many summers in the sun herds a couple of buffaloes into the water. A small boy jumps in after them with a shout. When you pass by they stare at you silently and shyly smile.

This land belonged to my father’s family once. Lush green and healthy land, acres of rolling country. The houses and cottages that dot the land formed part of the estate. Does the family own any of it now? My father wouldn’t know. He left Kerala after school and he no longer knows who owns what, and no one’s going to tell him. My grandmother can’t. She’s old and asthmatic and lives in a distant past inside her head. Reform and the new laws have in her own lifetime seen her move from feudal over lordship to being a trustee of an entangled legacy. She now lives in a small cottage with a daughter and a dog. Occasionally her sons drop in to check on her well-being. She will not go with them to the city. We talk of old times and new times.

My mother wants to visit the big house where other relatives of my father stay. I don’t particularly know any of them, our ties are distant, but my mother is a stickler for the disappearing protocols and courtesies of the old joint family system. I borrow my uncle’s motorcycle and double my mother to the big house. This was the house of my childhood memories. The wooden rafters are still grim and the courtyard is still house to a brooding silence. The years have not diminished the house. In a curious way I’m glad. Many times in different places, I have returned to the places of my childhood and they have usually been lesser than I’d remembered. But here, the big house still broods on the farmlands. The mango and jack trees and the inevitable coconut palms cannot soften the severity of its lines nor lighten its demeanor.

But in the afternoon sun, the courtyard is bright and a child’s laughter brightens the murmuring silence. I pass through a darkened room and overcome by a childhood impulse, I flick the lamp switch. Light pours out of a sixty-watt bulb. My cousins laugh when I tell them about my memories of shadows in the lamplight when we were children here together. They thump me on the back and tell me I’ve been away too long. Times have changed, they say.

Of course they have.

And yet. The land has changed hands and now the government, not the landlord collects the taxes. But when you walk on the fields in Adakkaputhur, you still sometimes pause and look back over your shoulder for no reason. This is a deep country and memories are long. The men are indolent, hard, and hint of licentiousness. The women are strong and suffering. At dusk, when night approaches from the darkening hills and when the fields are empty, you tend to walk a faster step to the homestead. The confidence of day is now prey to the uncertainties of the night. And when night falls on the fields and the courtyards of Adakkaputhur, the lamplight still casts shadows in the dark.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated.